Maybe it’s just me, but watermelon season seems to hit suddenly each year in North Carolina. Just when we’re starting to get over the July peaches, we arrive at the farmer’s market and—oh! There are piles of beautiful melons. This year I found myself on the other side of the market stand for the first time, selling watermelons that my partner and I had grown ourselves.

I was a little surprised by how much mysticism surrounds the watermelon. Confident customers shared their grandma’s surefire way of picking a perfect melon. Less certain folks often asked, “How do I pick a ripe watermelon?” Or they requested, “Pick me out a good melon.” I have to chuckle. As I learned, those were the questions that we, the farmers, had to answer before ever leaving the field.

Melon Myths

You see, it’s really not up to the customer to choose a good watermelon. This burden lies almost entirely on the farmer—from the time of planting to the moment of harvest.

You’d think otherwise, with all the illustrated guides that populate summertime Facebook feeds, all touting “The Best Tips for Picking Out a Good Watermelon!” Now that I’ve grown watermelons myself, I know they’re wildly inaccurate. Here are just a few of the outrageous myths I’ve heard about watermelon ripeness.

- More “webbing” indicates a sweeter melon

There is no such correlation. “Webbing” refers to brown scrapes or blemishes on the watermelon’s rind. They are simply the plant’s scars and stretch marks. Their presence has nothing to do with sweetness, but instead the melon’s long and storied life from seed to harvest.

- Look for a dull or dark complexion

The color and shine of a melon can vary a lot between varieties. A dark forest green Sugar Baby is not necessarily sweeter than a boldly striped Crimson Sweet. Now, a change in complexion might be a clue to a grower that a melon is approaching harvest time, but I dare you as a shopper to tell the difference between melons at the store. They look more or less the same, because they’re the same variety, same crop, and harvested at the same time.

- Check for a dried out stem

I think I know where this myth comes from (and I discuss it further on). But a dried up stem might only indicate that your melon has been hanging around for a while, or that the vine began drying out before harvest. Not necessarily an indicator of sweetness or ripeness. Plus this tip doesn’t safeguard against picking an overripe melon.

- There are “male” and “female” watermelons, they have different shapes, and one is sweeter than the other

If I ever find the person who started this most egregious of myths, I might bonk them on the head with a watermelon. Repeat after me: melons do not have genders. Perhaps this idea stems from a misunderstanding of plant biology (learn how it really works here). Now, watermelons do come in all shapes and sizes, but this depends entirely on variety. Sorry to say, but there are no boy and girl melons—but you can pretend if that makes you happy.

How Watermelon Ripeness Works

If you’re a melon shopper, I will tell you a few things you can look for later in the article. But first, I want to share the farmer’s perspective.

Watermelons are different from some fruits (including other melons like cantaloupe or honeydew) in that they do not continue to ripen after they’re cut from the vine. This, combined with their thick protective rinds, makes them a profitable fruit that stores well until hitting the market.

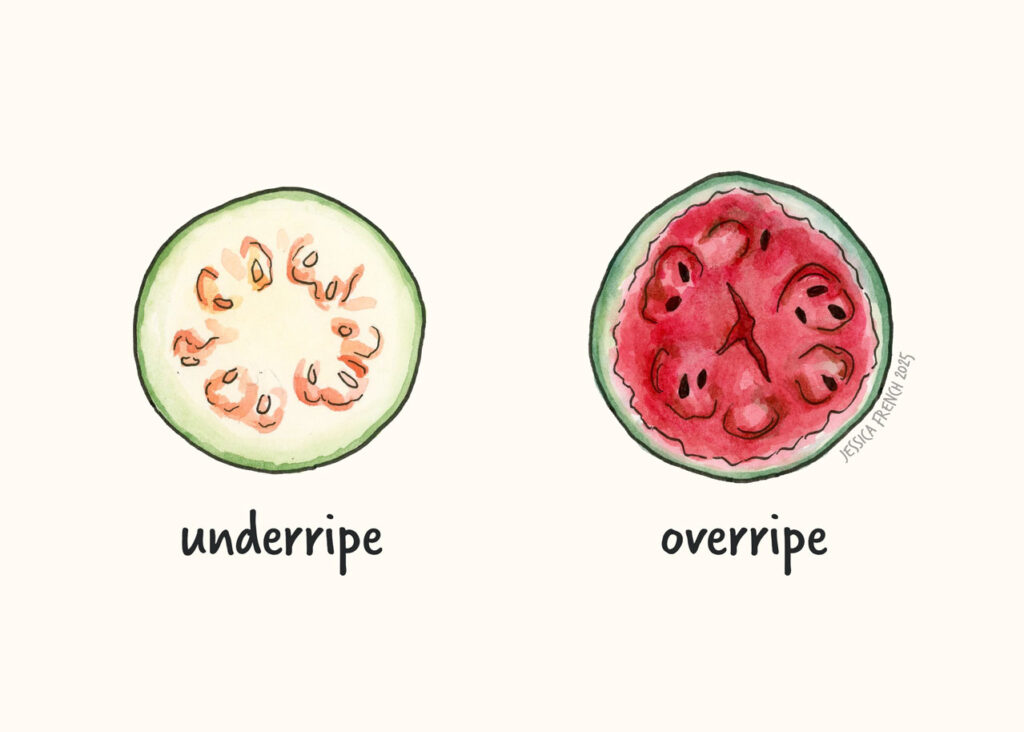

Watermelons also don’t have one single tell for ripeness. For instance, a cantaloupe is ripe when it can be pulled from the vine with a gentle tug (referred to as “slipping”). Not the case for watermelon–they will never “slip” off. This means that growing watermelon requires some knowledge and experience to harvest correctly. An underripe melon will essentially be a ball of rind, while an overripe melon will be a bowl of, uh…soup. The worst smelling soup on earth.

When to Harvest a Watermelon – Farmer Wisdom

As first time watermelon growers, we were rightfully nervous about cutting the first melon from the vine. The rampant myths didn’t help ease our anxiety. So we turned to more experienced farmers for advice. The responses varied a little (again, not every sign will appear in every ripe melon), but I boiled it down to four things:

- Days to maturity

This may be obvious to those gardeners who are fastidiously organized, but for the scatterbrained among us: try to find your seed packet and check the days to maturity for your variety. If you’re approaching that date, that’s a good clue that your melons may be ripe. Who knew seed producers actually research this stuff?

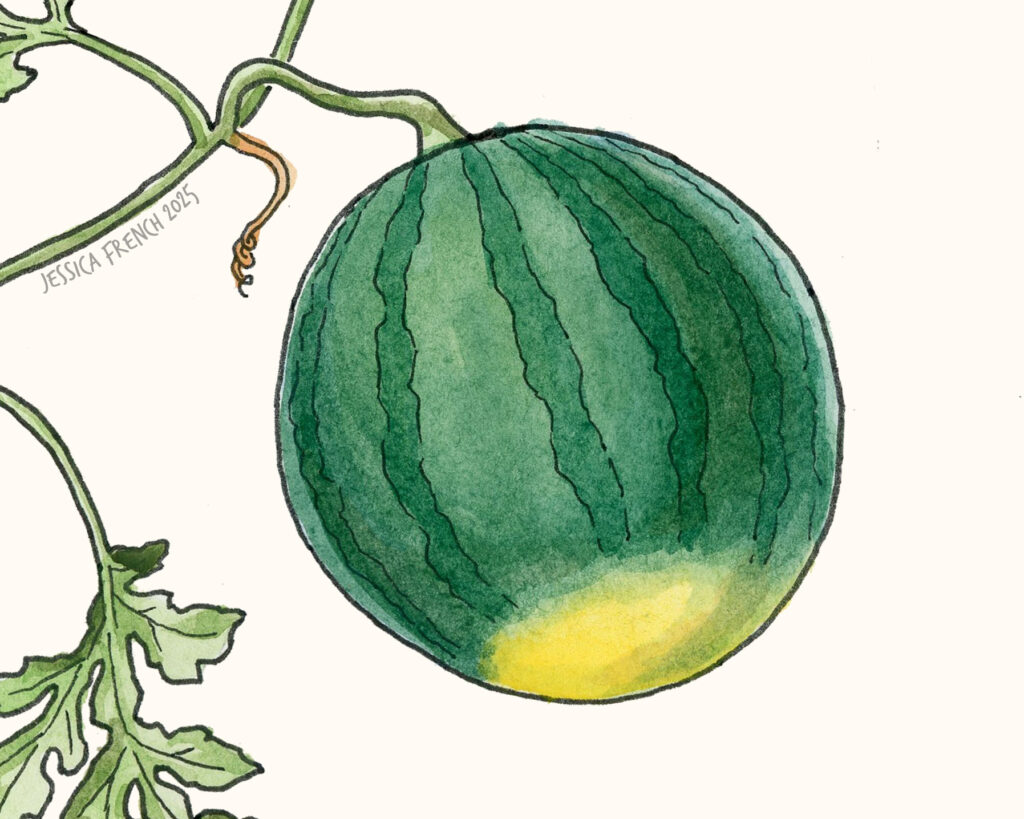

- The ground spot

Grab the nearest watermelon and turn it over. You’ll see a pale patch on the rind, right where it was resting on the earth. This is known as the ground spot. In most commercial watermelons, this spot will start out white, then gradually turn to yellow or orange when the melon is ripe. This is a fairly reliable trick for melon shoppers. As a grower, however, I’ve found this is a little iffy depending on the variety. For example, the popular Sugar Baby watermelon often has a glowing yellow spot well before it’s actually ripe. In contrast, the old-fashioned Charleston Gray is so pale that no ground spot may ever be visible. So don’t stop here.

- A dried up tendril

At each node along the vine (and yes, node is a botanical term), you’ll see a leaf branching from it, and you’ll also see a small tendril. These tendrils are what the plant uses to grab onto its surroundings to support itself. There is such a tendril right at the node where your watermelon’s stem is attached to the vine. This tendril starts out green, but eventually will dry out completely and turn a crispy brown. Keep an eye on your melon’s tendril, and once it has turned dry and brittle, that’s a good indication the melon at that spot is ripe.

- Softness of the melon

Several farmers told me that gently pressing on the melon’s stem end is a good way to test ripeness. Hard and unyielding signals a green melon, whereas one that “gives” a little will be riper.

- The Sound

Gently knock on the melon and listen for the sound. An underripe melon will produce a dull, solid sound, whereas a ripe one will have a clearer vibrant “ring.” One farmer put it like this: “Unripe sounds like ‘think,’ half-ripe sounds like ‘thank,’ and ripe sounds like ‘thunk.’” Now, I have tried this trick myself many times over, but still find it impossible to tell ripeness by sound. Even the USDA seems to think this test is just an old wives’ tale. Yet it was so ubiquitous among the farmers I asked, that I can’t help but think it must be a superpower a farmer unlocks after many, many seasons.

Practice Makes Perfect

Though all of these tests have relevance, more than one sign is usually seen in a watermelon that is ripe, and not every ripe melon will exhibit all of these signs. The best teacher in this matter is experience. As W. Atlee Burpee wrote back in 1909: “[If] there is any doubt in your mind about the ripeness of the melon, cut it open, and the experience gained will be sufficient compensation for the loss of the melon.”

I found this to be true in my first season growing watermelons. Nervous and unsure, we cracked open more than a few perfectly saleable melons and ended up eating them ourselves. Yet I have no complaints about the steady stream of delicious, juicy watermelon that seemed to fill my fridge every week of July and August.

Shopping for the Perfect Melon

For those who will never in a million years find themselves with a melon vine in their backyard, I promised I’d tell you what you can look for when shopping for a melon.

The ground spot test, as I said, is a pretty good method for picking a store melon. If faced with two otherwise identical melons, pick the one with the yellower ground spot.

Beyond that, however, there is little the buyer has control over. A good melon is grown with proper fertilization, ideal temperature, and controlled watering throughout the entire season. These are all things that even the farmer may struggle to control, let alone the shopper at the market. When faced with a bin of melons in the produce department, you’ll find that since most of them came from the same crop, there is little to tell each one apart. One season of bad weather may produce whole crops of mediocre melons.

My best advice is to buy watermelon when it’s in season, and if you can, buy one from a local grower. Local and in-season no melons are less likely to have been sitting in storage, and should have better texture and peak sweetness. Plus you may find that old Farmer Harold at the market grows unusual heirloom varieties that have superior tastes, textures, or even fun colors.

But for old Harold’s sake, I hope that you will never again fall for a cleverly designed infographic on Facebook insisting that there are “boy” and “girl” melons.